Delicacy That Enables Us To Accept the Impossible: Introducing the Poetry of Julia B. Levine and the Art of Anna Ticho

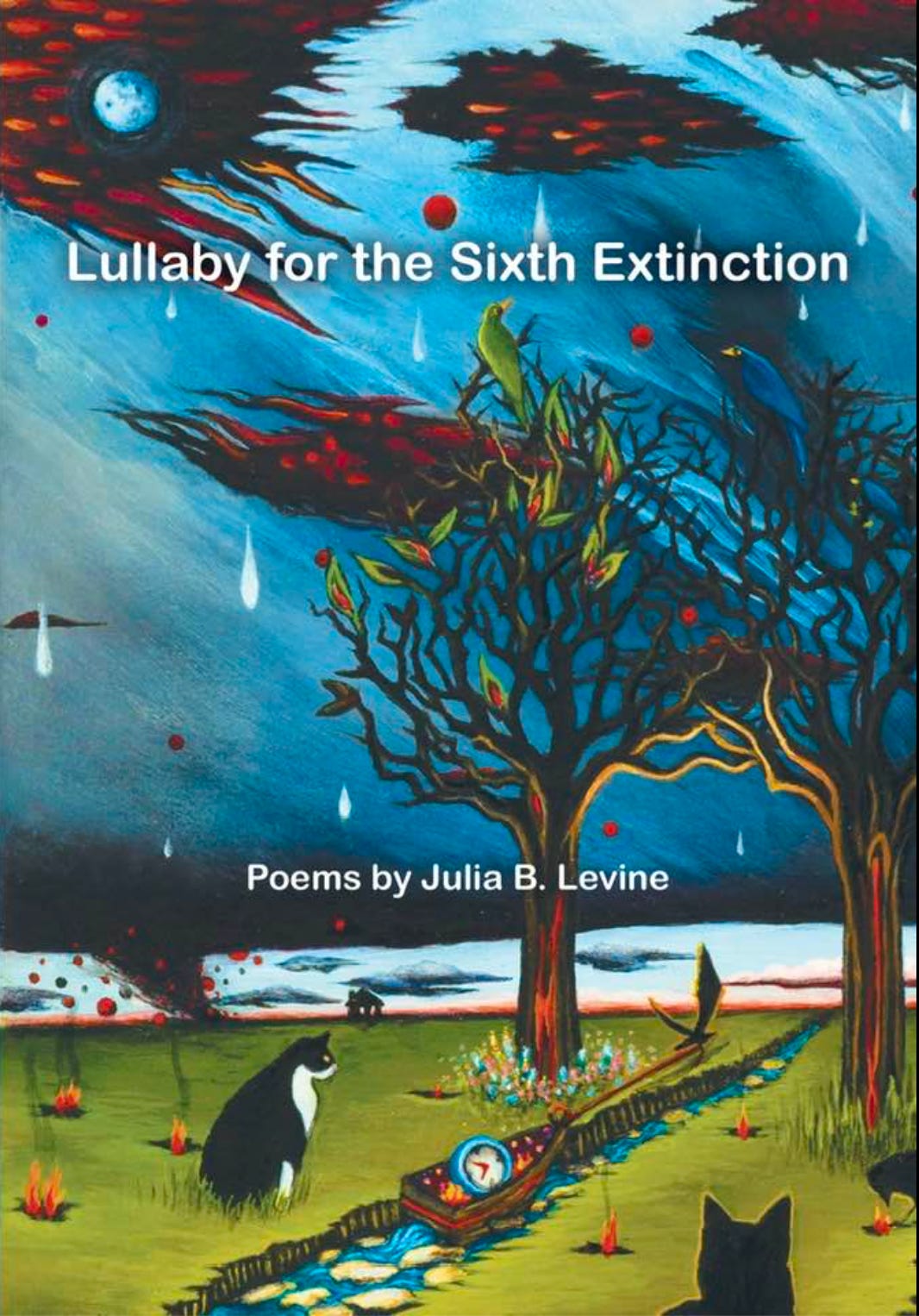

I have long loved Julia Levine’s poems. They move with such a quiet and delicate touch; the natural world is exposed in all of its loveliness and all of its torture. So too Julia’s life. These poems, some of which will be included in Julia’s upcoming chapbook Lullaby for the Sixth Extinction, due out in fall, are about the travail of watching her infant grandson suffer a cancer diagnoses.

This world continues on. The sun rises and sets. And its lovely. Every time. Everyday. And that is reality too, alongside all that comes inbetween and isn’t beautiful. Or even acceptable. Yes, war. Yes, famine. But also what isn’t man made: the pure suffering of a sick child.

Aubade with Fig Wasp and Fire It is not the stone angel in our yard hiding his eroded face under a wing. Not even the three blacktail deer bowing this morning to spring’s fierce green. No, it’s the Mountain bluebird overwintering down by the neighbor’s creek, that takes me back to that night alone in the Holy City, listening for eternity. I was 21, barely grown, waiting for God to tell me what came next, though what I heard was a muezzin in the dark, calling the faithful to prayer over a loudspeaker. And that ancient song swelling inside a closet-size, rented room, felt like nakedness I carried into what happened years later, when you picked a ripe fig from your tree and I tasted a seeded, sexual sweetness. Afterwards, you told me how a pollinating wasp crawls into the fig’s inflorescence and mates and dies in that cramped darkness, while most of her brood flies out. It takes so long to learn divinity is the province of the least among us, willing to sacrifice everything for the kingdom. O merciful outpost of aging, it takes decades to be properly stung by the idea of death setting fire to all our memories at once, leaving us with bonemeal and grizzled ash instead of a haunting voice in a minaret, or figs grown around the graves of captive wasps, even our own bodies formed by the eulogies we’ve had to stand up and give. Then today the Mountain bluebird setting down such brilliance in our plum tree, a few fallen stars shaken out in pink-white petals. And not simply the bird itself, but how you take me with you from one world into another, saying, Look, just beyond the fence, do you see it?, and I do.

Aubade in Late America Napa County’s largest lake covers 1.6 million acre-feet— and submerged a fertile valley and an entire town named Monticello. ‘Lost Under Lake Berryessa’, Alta Journal, 2019 The regime arrests a judge, disappears a child or two, and then it’s sunrise on a Thursday and we hike the canyon brilliant with lupine, winding alum. Around us, the steep hills burnt clean of oaks that won’t return. Though it seems a year, it was a week ago, that our grown daughters asked, How will we know before it’s too late to leave? And where will we go? Everywhere the sound of Cold Creek pouring over boulders. This late spring light sharpening the clouds. There’s a giant dam the next canyon over, and under it a sunken swing set gliding back and forth, dinner plates clattering across the deep lake-floor. I don’t know, but that last night before starting over, did the families stare out at their barns, vineyards, a gelding running frightened through the orchard? Too late to understand this was not a river, but the idea of one pouring a reservoir over their land, their homes. Time as a silence that catches hold. I mean, even at the end, was it too soon to believe it could be true—all those fields of wheat shining before them, lifted and light-spilled. Someone swearing, It can’t happen. Never will.

Mud and Justice You know how well it works to be told, Don’t think about it, he’ll be fine, while death lurks in the distance, silent as the fireworks we watched, glassed-in, from the top of the oncology pediatric ward, where chemo burned my grandson, thinned him to bone. Yet his first word, More. You know how we want to believe that whatever is torn from us leaves behind a riverbed, waiting to be filled again, and that it will come, the reparative rain, gleaming like our boy on his new legs climbing the garden steps, saying More, more, shattering us with his joy. You know we don’t get to choose who we love, and maybe you know too, how doubled is the going forward, the going back, the way one threat recalls another, how this morning, watching him lick dark streaks of dirt on his hands, I remember the mud I lay face down in after it was done. You know there is a place inside us that carries sadness for this world, for death arriving at hello, my grandson’s little body dressed in a hospital gown printed with rainbows. Of course we want to believe babies don’t endure a year of chemo just to die, or that rapists won’t remain at large, hunting in daylight, but the truth is, justice is a lie. While mercy is another story— as small as how I remember best the bitter taste of mud, not the gun at my temple, not the stranger’s weight against mine. And mercy as large as that morning I returned from the rape exam to hold my daughter in my arms, a flesh and bone joy in the face of death working its way through time like rain restoring the river’s scar.

Midsummer Argument with Fester and Rot Early morning, and hot. A starling chick silent in the road. Gravity too solemn without song. The fledgling fallen from her nest onto asphalt, tossed into the bullseye of the next eagle circling overhead. Look away, I tell myself, walk on. But I’ve turned back instead to snap two giant leaves from the maples, wrap the chick in a mildew-spotted, green shroud. Not because of kindness, no. It is, at heart, a bone I must pick with the nature of suffering. With the terror I feel at the idea of God, if that is how the starling mistakes me, as I lift her into my palm, carry her into the grotto’s shade to die. I’m sorry if this is all wrong, I whisper to the fledgling. Because who am I to mess with the merciless machinery of this world? Maybe this is the nature of suffering too. The sorrow we’ve been asked to bear without instruction on how to help. Desolate, the echoing thud in my body as the chick is soon to be taken from hers. The world a wound the closer that you come. Carrion, the song the starling will come to sing. Always a darker lament below.

If Math Might Hold the Terror Down Just outside the nurses’ station, at every shift change my grandson’s cancer maps a geographical territory on a white board in black erasable marker & milliliters of milk & numbers of diapers & bright pink bags of chemo between naps & loudspeaker codes we learn to decipher—pink for stolen baby, blue for heart attack, red for mass shooter. Every minute measured & yet it startles how every day vanishes whole though the hours must be opening correctly somewhere else— maybe a city park with babies under trees in wind, a cricket outside the coffee shop singing in time to a concerto. Sometimes I drive out to Land’s End & stand on the sandstone cliffs above the sea to be reminded of larger griefs— our planet in trouble with nitrogen & carbon, the St Lucia racer snake down to 20, bluebird of paradise subtracted along with glacial ice. In this year of maybe-not, maybe all that saves us is the way we know to count the endangered species (near 700 now), because everywhere my grandson’s red circuitry goes death trails like an understudy, death in the calendar, death pixelated in every text my daughter sends. As if a negative number had escaped visceral and uncaged & shadowing every hour, even today, months after he’s left the hospital, all plump & babbling at his weekly outpatient visit, the doctor laughing at his antics (& squawking with excitement, the baby pulls plastic purple gloves from a box one by one) until she reads his lab-work & time sparks sputters out. This is how it started a year ago: his blood counted and sorted, hemoglobin & neutrophils too low, time breaking down, the doctor saying, Don’t worry it’s probably nothing, time snagged on death’s barbed & shaky read of light’s errand, (& time wasn’t it already agreed upon?) time refusing to move on.

After Learning the Transplant May Have Failed

How hurried the light after rain, the snow

geese wheeling across blue miles of wetlands,

the ponds sun-steeped gold in late afternoon.

If to pray is to ask and know there is

no one and nothing to answer, then

I will ask only to lie down in wet grass

wingless under this flyway, this vast sky

given to passage, I will ask please embed him

in the crossing over, please give my grandson

time in the only once of it. If to pray

is to plead, I will beg the dusk that worries

these wild flocks as they rise and fall

and cannot settle, will beg for him to stay

long among us, please it’s late, hurry now.Coda with Bird and Paper Lantern Before she died, my mother told me I could do anything. So I’ve taught myself to fly in dreams. You need only a downward slope, a running start, your arms held out like wings. The lift is easy, the steering hard. I often slam my head against arches, a hidden casement, a ceiling fan before I reach the sky. The way we thought my grandson would be snuffed out by chemo, by the cancer in his blood, before he was a year old. Wake up!, he loves to say now. Wake up! Today he hit me because I wouldn’t let him stand alone in the street. Luckily he’s easy to distract. I showed him two fish drawn on the sidewalk. They looked as if they were flying above concrete. See, I pointed and he used this sideways wave he invented to say fish. As well as bird. Because language is like flying too. How it can carry you away from loneliness. These days my grandson is an ecstatic. His body a whirl of motion until bed, where he cries himself to sleep. It goes so fast, enjoy it while you can, everyone tells my daughter. Wake up, wake up, I think. His cancer broke us into different things. For me, a bird at night, that doesn’t remember how to rise without hitting itself hard on the way out. For my daughter, a paper lantern carrying flame. She knows to set into water, alive and burning, however long it lasts, however far it goes.

The Second Coming Our family’s faith died long ago, though it’s God my daughter damns to hell, leaning across the guardrail of the hospital’s rooftop garden, before letting me curl around her on the ground where she lies. Last night when the nurse found my daughter sobbing, she said, At your son’s wedding, this will be a story that you tell. And yet, inside the ICU, my grandson, in a white crib, bleeds into his brain, with no one to explain his whimper, his erratic heartrate, the little melody of matter he will always sing in me. No one but the night doctor mumbling that our boy might die. Still, let’s say he lives. That one day I’ll tell him how his grandfather, his aunt and I lay down on dirt beside his mother, our faces turned up to rain, a darkening grey. We listened to helicopters taking off, their roaring like angels come to rid the evening of its wolves. Hours dragged through a black to whitening sky. When we walked back inside, wet and cold, we huddled around my grandson’s crib as if to warm our hands at a fire. And then the story of his second coming. This happened so long ago, I’ll begin, it was once upon a time.

Julia B. Levine’s poetry has won many awards, including the 2024 Wolfson Press Prize for her chapbook, Lullaby for the Sixth Extinction, due out in fall, 2025, as well as the 2015 Northern California Book Award in Poetry for her fourth collection, Small Disasters Seen in Sunlight, (LSU, 2014). Recently she has won a 2024 Pushcart Prize, the 2024 Terrain Poetry Prize, the 2023 Oran Perry Burke Award from The Southern Review, the 2022 Steve Kowit Poetry Prize, the 2020 Bellevue Literary Review Poetry Award, as well as a 2022 American Academy of Poetry Poet Laureate Fellowship for her work in building resiliency in teenagers related to climate change through poetry, science and technology. Her work has appeared in many literary journals, including, Ploughshares, The Southern Review, The Missouri Review, The Nation and Prairie Schooner. She received a Ph.D. in clinical psychology from University of California, Berkeley and an MFA in poetry from Pacific University. sites.google.com/view/juliablevine

Anna Ticho was born in Brno, Moravia, and immigrated to Palestine in 1912. Jerusalem and its environs enchanted her and she drew powerful and precise drawings of the city in charcoal crayon. Ticho’s love of Jerusalem is vividly expressed in her landscapes: bare rocky hills, stones, old trees, and faces—the lined topography of its people -- all comprise her picture of the city. Her works were first shown at the historic exhibition of local artists at David’s Tower in the Old City of Jerusalem in 1922 and later in many solo exhibitions. She was a co-founder of the New Bezalel School, today the Bezalel Academy of Art, and the recipient of many honorary titles and awards, including the 1965 Art Prize of the City of Jerusalem.

From the moment she arrived in Jerusalem in 1912 till the day she died in 1980, Anna Ticho lived in and lovingly portrayed it in paint, pen and ink, charcoal, pastel and pencil.

“I came to Jerusalem when it was still ‘virgin territory,’ with vast, breathtakingly beautiful vistas … I was impressed by the grandeur of the scenery, the bare hills, the large, ancient olives trees, and the cleft slopes … the sense of solitude and eternity.”

What breathtaking, precise poems. Levine and Ticho are masterful artists. Thank you for being the bridge from them to me. A blessing.

I am so taken by both Julia Levine's poetry and Anna Ticho's artworks. The poems' lyricism in the face of suffering is striking; the artworks provide the quiet in which to contemplate how words grant us the possibilities of both beginnings and ends.