Hope Against Hope: Introducing the Poetry of Caleb Horowitz and the Paintings of Reuven Rubin

I am sitting on the downstairs porch watching the moon eclipse from bright to dark to red. The news rumbles on in the apartment behind me. The bats are flying back and forth between the fig trees, so close I can feel the breeze from their wings on my face. My partner tells me that all the men from town are gone. When he went to the kiosk where they meet to share a drink and some chat, the last one of the group, Saffi, a slight and delicate man, took his army bag and was on his way. To Gaza. How is it possible that this terrible terrible war continues? Meanwhile we are all protesting. Protesting and writing: writing as protest: against war, against death, against this life itself where we are all left torn and confused. The poet Caleb Horowitz writes too from the place where hope is as dark as an eclipsed moon:

but when the Messiah comes, I will be at the dog races, watching my dog lose his race forever and ever.

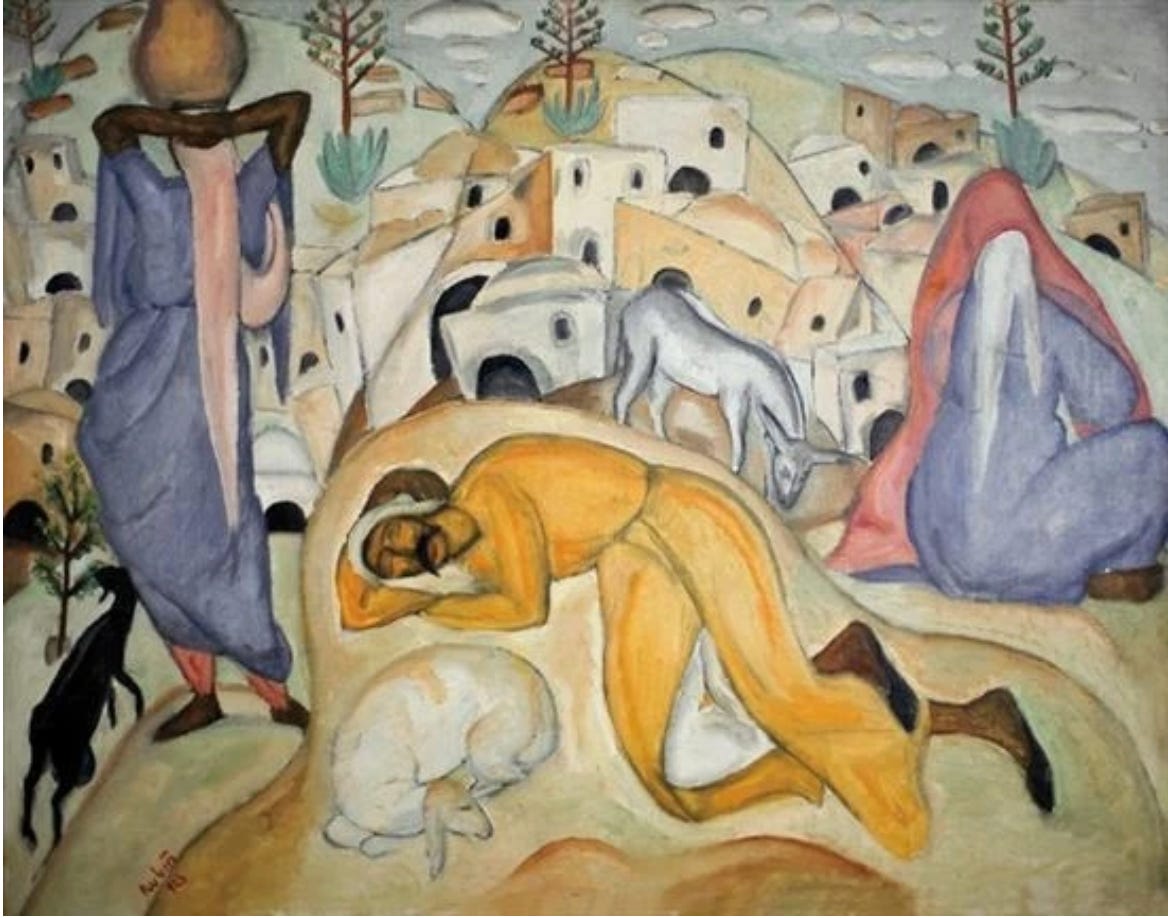

Reuven Rubin in 1950 painted Jesus as the special guest at the first Passover seder in Jerusalem. That sign of hope in the midst of a painting of all kinds of Jews. How did we get from that hope to here? To now? To this?

Please let this war end now. Please let it end.

Exodus

Today I drove past the waterfowl impoundment sign,

and I thought of you,

that joke we have about imprisoning ducks,

and the week you stayed on my couch

while the summer ached on feverish.

We made cocktails every night until we used up all the gin,

watched science fiction and complained

every time the plot slipped into inanity.

You needed to go to the doctor,

and you needed someone to tell you

that you needed to go to the doctor.

A week went by.

We’ve never known how to care for each other

the way brothers should.

Our mother named us

for the two spies who inherited

the Promised Land, but

I think if Joshua and Caleb had been brothers,

G-d would have made them fight for it—

In the Torah, there are no happy brothers.

Even Aaron, the best of us,

melted gold into god, built something horrid

in the fearful place where he felt his brother’s absence.

And when our parents made you

schedule a doctor’s appointment,

and you took the train back to D.C.,

and I returned to my condo

and the half a bottle of absinthe

and the bedsheet on the couch—

I went online and searched

for a midrash that could tell me

the central mistake of Exodus

was that Moses climbed

Mount Sinai alone.In the Games I Play, the World is Always Ending after Majora’s Mask In this one, it’s the moon, enchanted to hurtle angry down to Earth, and I am a little boy in green collecting everything I can hold in these chubby child hands: small keys and dungeon maps, a compass, glass bottles to hold milk or insects or the eggs of a dying fish, and even though we have three days left until the moon collides with everything anyone has ever loved, the world is wild and beautiful with me in it. Seventy-two hours, and I am at the racetrack, betting on dogs, and the blue dog I bet on is running, kicking up dirt. The rabbis say, If the earth ends tomorrow, still, plant a sapling today. But as the earth is ending, I am gambling on a dog that cannot win. Statistically, this dog cannot win. The people of the internet have crunched the numbers, and the blue dog is programmed not to be good enough. The game must be manipulated, the conditions made more favorable, for the little blue dog to ever stand a chance. But I am following the rules—I manipulate nothing. I want to explain this game to you, this video game where you have three days to stop the moon from being pulled into the earth, where it will ruin all that we’ve built. But I think you already know it: the way the mayor sits in his office and does nothing, the way the child who calls down the moon to destroy the planet is so terribly grieved into violence, the way that we all look up at this apocalypse and return to small things. And here I am watching a long video of a man who has painstakingly manipulated the game so that the blue dog can win, and while I watch, outside the window of my home there perhaps hurtles some moon— it does not have to be a moon— toward our little planet, and there is something, I think to be said for the way that we do not stop. For the mailman to never stop delivering, should the Earth cease to earth around him, for this stranger on the internet to rewire the fabric of the gameworld so that the blue dog can win his race, for the boy in green to shore up these small trinkets against apocalypse— we are bad at fixing the right things— this planet, that falling moon. But we are good at something. I used to think that when the rabbis said to plant the tree, they wanted us to understand that there is a future beyond oblivion, that that future must be prepared for. But a single tree is not so important. Maybe the point is not to neglect any of it at all, and by “it” I mean the bugs and the bottles, the wild fields and everything you can grab with your two child-hands. And this is not an excuse, so do not forgive me— please, don’t forgive any of us— but when the Messiah comes, I will be at the dog races, watching my dog lose his race forever and ever.

Purim 5785

And I’m the one dressed as a black and white cookie

by the wall wishing I knew any of these Jews, thinking

these drinks are weak but the Megillah is short—

and the rabbi and his wife are taxi cabs, and he

shuckles his way through Esther in a language

I think I will never learn and I speak with Rosie the Riveter

about poetry and pediatrics while the two tall blonde

Subway Rats speak of their time in the army and

isn’t it always embarrassing explaining your costume,

but perhaps less embarrassing than dressing

as the Statue of Liberty or “a New York Businessman”

like a coward—and this man eating the pretzel is

an artist, shows me cartoons on his phone—an artist

dressed as an artist, which is not a costume but is still better

than the Statue of Liberty or her boyfriend with the paper sign

that says, “I fell in love with the state of liberty,” typo and all,

and when the New York Times Crossword says

“Ah, you’re a black and white cookie”

without having to be told, I am filled with such longing

that quickly shifts into a kind of pathetic loneliness

like the sardine in the corner shedding his fish scales to reveal

just a person, just a person in a shirt and jeans.The Book of Elisha, as Told By Jonah

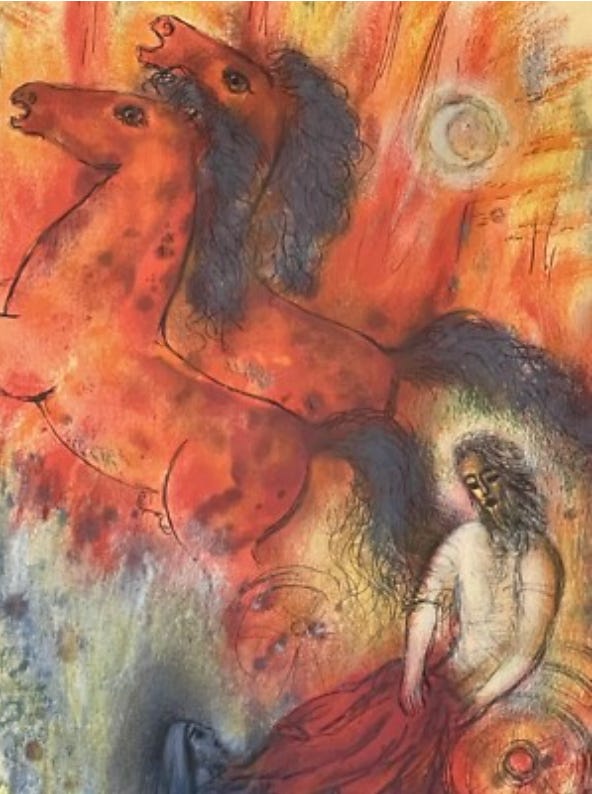

When G-d took Elijah from you,

you took your teacher’s coat

and tied it round your waist.

For years you told me the story

of the chariot and burning horses that carried

that great man

up into the burgeoning sky.

There was a time I believed

I could smell the char of G-d

in your jacket.

When I was young and Elijah

raised me up from the dead

I knew then I would speak

the Language of the Dead forever.

And you never asked me then

“What of Death, can you tell me, Jonah?”

Were you uncurious or just polite?

But my mother was all questions—

“Before G-d’s man brought you back,

Jonah, where did you go?”

And she sent me with you

for my second childhood,

and all that would come after.

You taught me to heal people:

the famished, the leprous, but never

the dead—and at night,

I dreamed of the three of us—

an unbroken chain of prophets,

healing everything we touched.

They say that the day G-d took him from you,

the people around you felt it

coming like a storm in their bones.

You followed Elijah from city to city,

avoiding the crowds—swarms

of people asking questions

they did not deserve to know the answers to:

“Do you know that G-d will steal

the one you love away from you today?”

“I know it too; be silent.”

Suddenly, you had questions for me.

Questions about death, about

in-between places.

“Tell me Jonah, what have you learned?”

What I have learned of the little

parchment stretched taut between

life and death is that

G-d does not ask

before He makes a small puncture

and ushers one of us there

or back again.

And neither did Elijah

and neither do you.

You were impossible in those days—

preoccupied with measuring

divinity’s exact dimensions,

obsessed with what G-d had taken from you.

Every day began with a chariot and ended

with you like a pale shadow on the shore.

But some evenings, your eyes softened,

and you let me run my fingers through his cloak—

“How are you, Jonah, son of Amittai,

my disciple, my friend?”—

and in those moments,

perhaps I was happy.

In the years after I knew you,

the scriptures say that I fled

from G-d to Tarshish,

and I did, but that night, as I slept

below deck in the wooden belly of things,

and the storm wrapped around us like a womb,

I did not remember anything about death,

about whatever brink Elijah pulled me back from.

I dreamt of you,

you who I had not thought of in months,

ascending on a rain-soaked chariot, your arm

lit by a slice of lightning,

your damp cloak tumbling

from the sky.Caleb Horowitz is a North Carolinian high school teacher and poet. He is working on a manuscript responding to Moby-Dick and the Biblical Jonah. You can find his writing with The Jewish Book Council, Gashmius Magazine, Verklempt!, and Psaltery & Lyre.

Reuven Rubin (1893–1974) was a Romanian-born Israeli painter who was a pioneer of the Eretz-Yisrael style, known for his vibrant landscapes, figures, and biblical themes of the Israeli land, which he portrayed with radiant, earthy colors and expressive forms. He studied in Jerusalem, Paris, and New York, returning to Mandatory Palestine in 1923 to settle in Tel Aviv and help define early Israeli art. Rubin received international acclaim and was awarded the Israel Prize in 1974, the year of his death. His house in Tel Aviv was established as the Rubin House Museum after his passing.

Caleb, these poems are so ambitious and each one lands (I mean LANDS!) in such a way as to break your heart and at the same time give you so much reason to hope.

This just floors me:

“What I have learned of the little

parchment stretched taut between

life and death is that

G-d does not ask

before He makes a small puncture

and ushers one of us there

or back again.”

And the little blue dog.

Beautifully presented and, as always, poems deserving more than one reading and gorgeous art.